What Is Beryl Used For

| Beryl | |

|---|---|

Three varieties of beryl (left to right): morganite, aquamarine and emerald | |

| General | |

| Category | Cyclosilicate |

| Formula (repeating unit of measurement) | Be three Al ii Si half-dozen O xviii |

| IMA symbol | Brl[ane] |

| Strunz classification | ix.CJ.05 |

| Crystal system | Hexagonal |

| Crystal form | Dihexagonal dipyramidal (half dozen/mmm) H-M symbol: (six/yard 2/m ii/g) |

| Infinite group | P6/mcc |

| Unit prison cell | a = 9.21 Å, c = 9.19 Å; Z = 2 |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 537.50 chiliad/mol |

| Color | Green, blue, yellow, colorless, pink, and others |

| Crystal addiction | Prismatic to tabular crystals; radial, columnar; granular to compact massive |

| Twinning | Rare |

| Cleavage | Imperfect on {0001} |

| Fracture | Conchoidal to irregular |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 7.5–viii |

| Luster | Vitreous to resinous |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to translucent |

| Specific gravity | Average 2.76 |

| Optical backdrop | Uniaxial (-) |

| Refractive index | nω = 1.564–1.595 nε = 1.568–1.602 |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.0040–0.0070 |

| Pleochroism | Weak to distinct |

| Ultraviolet fluorescence | None (some fracture filling materials used to ameliorate emerald's clarity do fluoresce, but the stone itself does non). Morganite has weak violet fluorescence. |

| References | [2] [3] [four] [five] : 112 |

Beryl ( BERR-əl) is a mineral composed of glucinium aluminium silicate with the chemical formula Be3Al2Si6O18.[6] Well-known varieties of beryl include emerald and aquamarine. Naturally occurring, hexagonal crystals of beryl tin can be up to several meters in size, but terminated crystals are relatively rare. Pure beryl is colorless, but it is frequently tinted past impurities; possible colors are green, blue, xanthous, pink, and red (the rarest). It is an ore source of beryllium.[7]

Main beryl producing countries

Etymology [edit]

The discussion beryl – Middle English: beril – is borrowed, via Old French: beryl and Latin: beryllus, from Ancient Greek βήρυλλος bḗryllos, which referred to a 'precious blue-green color-of-sea-water stone';[2] from Prakrit veruḷiya, veḷuriya 'beryl' (compare the pseudo-Sanskritization वैडूर्य vaiḍūrya 'cat's eye; jewel; lapis lazuli', traditionally explained every bit '(brought) from (the city of) Vidūra'),[8] which is ultimately of Dravidian origin, maybe from the proper noun of Belur or Velur, a town in Karnataka, southern India.[9] The term was later adopted for the mineral beryl more exclusively.

When the first eyeglasses were constructed in 13th-century Italy, the lenses were made of beryl (or of stone crystal) as glass could not be made clear enough. Consequently, glasses were named Brillen in German[10] (bril in Dutch and briller in Danish).

Deposits [edit]

Beryl is a mutual mineral, and it is widely distributed in nature. It found virtually commonly in granitic pegmatites, but also occurs in mica schists, such as those of the Ural Mountains, and in limestone in Colombia.[11] Information technology is less common in ordinary granite and is only infrequently establish in nepheline syenite. Beryl is often associated with tin and tungsten ore bodies formed as high-temperature hydrothermal veins. In granitic pegmatites, beryl is found in association with quartz, potassium feldspar, albite, muscovite, biotite, and tourmaline. Beryl is sometimes institute in metasomatic contacts of igneous intrusions with gneiss, schist, or carbonate rocks.[12] Common beryl, mined every bit beryllium ore, is found in small-scale deposits in many countries, but the master producers are Russia, Brazil, and the United States.[eleven]

New England's pegmatites accept produced some of the largest beryls establish, including one massive crystal from the Bumpus Quarry in Albany, Maine with dimensions 5.5 by 1.2 g (18.0 by 3.9 ft) with a mass of around 18 metric tons; it is New Hampshire's state mineral. Equally of 1999[update], the world's largest known naturally occurring crystal of whatsoever mineral is a crystal of beryl from Malakialina, Madagascar, 18 g (59 ft) long and 3.5 g (eleven ft) in diameter, and weighing 380,000 kg (840,000 lb).[13]

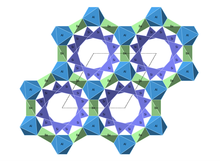

Crystal addiction and structure [edit]

Beryl crystal structure with view downwardly C centrality

Beryl belongs to the hexagonal crystal organisation. Normally beryl forms hexagonal columns but can also occur in massive habits. Every bit a cyclosilicate beryl incorporates rings of silicate tetrahedra of Si

six O

18 that are bundled in columns along the C axis and as parallel layers perpendicular to the C axis, forming channels along the C axis.[7] These channels permit a variety of ions, neutral atoms, and molecules to be incorporated into the crystal thus disrupting the overall accuse of the crystal permitting further substitutions in aluminium, silicon, and beryllium sites in the crystal structure.[7] These impurities give rise to the variety of colors of beryl that can exist found. Increasing alkali content inside the silicate ring channels causes increases to the refractive indices and birefringence.[14]

Human health impact [edit]

Beryl is a glucinium compound that is a known carcinogen with acute toxic furnishings leading to pneumonitis when inhaled.[15] Care must thus be used when mining, handling, and refining these gems.

Varieties [edit]

Aquamarine and maxixe [edit]

Aquamarine (from Latin: aqua marina, "sea water"[16]) is a blue or cyan variety of beryl. It occurs at most localities which yield ordinary beryl. The gem-gravel placer deposits of Sri Lanka comprise aquamarine. Green-yellow beryl, such equally that occurring in Brazil, is sometimes called chrysolite aquamarine.[17] The deep blue version of aquamarine is chosen maxixe.[18]

The stake blue colour of aquamarine is attributed to Fetwo+. Fethree+ ions produce gold-yellow color, and when both Feii+ and Atomic number 263+ are present, the color is a darker blue as in maxixe.[19] [twenty] Decoloration of maxixe by light or heat thus may exist due to the charge transfer between Ironiii+ and Fe2+.[21]

In the Usa, aquamarines can be found at the summit of Mt. Antero in the Sawatch Range in key Colorado, and in the New England and North Carolina pegmatites.[22] Aquamarines are also present in the state of Wyoming, aquamarine has been discovered in the Big Horn Mountains, near Pulverisation River Pass.[23] Another location within the United States is the Sawtooth Range almost Stanley, Idaho, although the minerals are within a wilderness area which prevents collecting.[24] In Brazil, in that location are mines in the states of Minas Gerais,[22] Espírito Santo, and Bahia, and minorly in Rio Grande do Norte.[25] The mines of Colombia, Madagascar, Russia,[22] Namibia,[26] Zambia,[27] Republic of malaŵi, Tanzania, and Republic of kenya[28] also produce aquamarine.

Emerald [edit]

Emerald is dark-green beryl, colored by around 2% chromium and sometimes vanadium.[29] [30] Near emeralds are highly included, so their brittleness (resistance to breakage) is classified as generally poor.,[31]

The modern English discussion "emerald" comes via Middle English emeraude, imported from modern French via Old French ésmeraude and Medieval Latin esmaraldus , from Latin smaragdus , from Greek σμάραγδος smaragdos meaning 'dark-green gem', from Hebrew ברקת bareket (one of the twelve stones in the Hoshen pectoral pendant of the Kohen HaGadol), pregnant 'lightning wink', referring to 'emerald', relating to Akkadian baraqtu, meaning 'emerald', and possibly relating to the Sanskrit word मरकत marakata, significant 'green'.[32] The Semitic give-and-take אזמרגד izmargad, meaning 'emerald', is a back-loan, deriving from Greek smaragdos.

Faceted emerald, 1.07ct, Republic of colombia

Emeralds in antiquity were mined by the Egyptians and in what is at present Republic of austria, likewise every bit Swat in contemporary Pakistan.[33] A rare type of emerald known as a trapiche emerald is occasionally plant in the mines of Republic of colombia. A trapiche emerald exhibits a "star" blueprint; it has raylike spokes of dark carbon impurities that give the emerald a six-pointed radial design. Information technology is named for the trapiche, a grinding bicycle used to procedure sugarcane in the region. Colombian emeralds are generally the near prized due to their transparency and burn. Some of the rarest emeralds come from the 2 main emerald belts in the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes: Muzo and Coscuez west of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, and Chivor and Somondoco to the due east. Fine emeralds are also found in other countries, such every bit Zambia, Brazil, Zimbabwe, Madagascar, Pakistan, India, Transitional islamic state of afghanistan and Russia. In the Usa, emeralds can be found in Hiddenite, North Carolina. In 1998, emeralds were discovered in Yukon.

Emerald is a rare and valuable gemstone and, as such, information technology has provided the incentive for developing constructed emeralds. Both hydrothermal[34] and flux-growth synthetics have been produced. The first commercially successful emerald synthesis process was that of Carroll Chatham.[35] The other large producer of flux emeralds was Pierre Gilson Sr., which has been on the marketplace since 1964. Gilson's emeralds are normally grown on natural colorless beryl seeds which go coated on both sides. Growth occurs at the charge per unit of 1 millimetre (0.039 in) per calendar month, a typical seven-month growth run producing emerald crystals of 7 mm of thickness.[36] The green color of emeralds is widely attributed to presence of Cr3+ ions.[37] [19] [20] Intensely dark-green beryls from Brazil, Zimbabwe and elsewhere in which the color is attributed to vanadium take as well been sold and certified equally emeralds.[38] [39] [40]

Golden beryl and heliodor [edit]

Faceted gilt beryl, 48.75 ct, Brazil

Gilded beryl can range in colors from pale yellow to a bright gold. Dissimilar emerald, gilded beryl generally has very few flaws. The term "gilt beryl" is sometimes synonymous with heliodor (from Greek hēlios – ἥλιος "sunday" + dōron – δῶρον "gift") but aureate beryl refers to pure yellow or golden yellow shades, while heliodor refers to the greenish-yellow shades. The aureate yellow color is attributed to Fe3+ ions.[29] [37] Both golden beryl and heliodor are used equally gems. Probably the largest cut gold beryl is the flawless 2054-carat stone on display in the Hall of Gems, Washington, D.C., U.s..[41]

Goshenite [edit]

Faceted goshenite, i.88 ct, Brazil

Colorless beryl is called goshenite. The name originates from Goshen, Massachusetts, where it was originally discovered. In the by, goshenite was used for manufacturing eyeglasses and lenses owing to its transparency. Nowadays, information technology is most commonly used for gemstone purposes.[42] [43]

The jewel value of goshenite is relatively low. However, goshenite can exist colored yellow, green, pink, blue and in intermediate colors past irradiating it with high-energy particles. The resulting color depends on the content of Ca, Sc, Ti, V, Fe, and Co impurities.[37]

Morganite [edit]

Faceted morganite, 2.01 ct, Brazil

Morganite, also known as "pink beryl", "rose beryl", "pink emerald" (which is not a legal term according to the new Federal Merchandise Commission Guidelines and Regulations), and "cesian (or caesian) beryl", is a rare light pink to rose-colored gem-quality diverseness of beryl. Orange/yellowish varieties of morganite can also be institute, and colour banding is common. It can be routinely rut treated to remove patches of yellow and is occasionally treated by irradiation to improve its colour. The pink color of morganite is attributed to Mnii+ ions.[29]

Scarlet beryl [edit]

Red beryl (formerly known as "bixbite" and marketed as "cherry emerald" or "ruby-red emerald" but notation that both latter terms involving "Emerald" terminology are now prohibited in the Us under Federal Trade Commission Regulations)[44] is a red variety of beryl. Information technology was offset described in 1904 for an occurrence, its blazon locality, at Maynard'south Merits (Pismire Knolls), Thomas Range, Juab County, Utah.[45] [46] The onetime synonym "bixbite" is deprecated from the CIBJO, because of the run a risk of confusion with the mineral bixbyite (both were named subsequently the mineralogist Maynard Bixby).[47] The nighttime ruby colour is attributed to Mn3+ ions.[29]

Faceted red beryl, 0.56 ct, Utah U.s.

Cerise beryl is very rare and has been reported merely from a scattering of locations: Wah Wah Mountains, Beaver Canton, Utah; Paramount Canyon and Round Mount, Sierra County, New Mexico, although the latter locality does not oft produce gem grade stones;[45] and Juab Canton, Utah. The greatest concentration of gem-form red beryl comes from the Cerise-Violet Claim in the Wah Wah Mountains of mid-western Utah, discovered in 1958 by Lamar Hodges, of Fillmore, Utah, while he was prospecting for uranium.[48] Red beryl has been known to be confused with pezzottaite, a caesium analog of beryl, that has been establish in Madagascar and more than recently Afghanistan; cut gems of the ii varieties can be distinguished from their difference in refractive index, and rough crystals can be easily distinguished by differing crystal systems (pezzottaite trigonal, ruby-red beryl hexagonal). Constructed cherry-red beryl is likewise produced.[49] Similar emerald and dissimilar most other varieties of beryl, ruby beryl is usually highly included.

While precious stone beryls are normally found in pegmatites and sure metamorphic stones, red beryl occurs in topaz-bearing rhyolites.[50] It is formed by crystallizing under low pressure and high temperature from a pneumatolytic phase along fractures or inside nigh-surface miarolitic cavities of the rhyolite. Associated minerals include bixbyite, quartz, orthoclase, topaz, spessartine, pseudobrookite and hematite.[46]

Run across likewise [edit]

- Chrysoberyl – Mineral or gemstone of glucinium aluminate

- List of minerals – Listing of minerals for which there are manufactures on Wikipedia

References [edit]

- ^ Warr, Fifty.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ a b "Beryl". mindat.org. Archived from the original on 26 Oct 2007.

- ^ "Beryl Mineral Data". webmineral.org. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008.

- ^ "Beryl" (PDF). Mineral Data Publishing. 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 November 2011.

- ^ Schumann, Walter (2009). Gemstones of the World. Sterling Publishing Co. ISBN978-1-402-76829-three. Archived from the original on 20 Nov 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Beryl". www.minerals.net . Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ a b c Klein, Cornelis; Dutrow, Barbara; Dana, James Dwight (2007). The Transmission of Mineral Science : (afterwards James D. Dana) (23rd ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: J. Wiley. ISBN978-0-471-72157-4. OCLC 76798190.

- ^ Walter West. Skeat; Walter William Skeat (1993). The Concise Dictionary of English Etymology. Wordsworth Editions. p. 36. ISBN978-i-85326-311-8.

- ^ "beryl". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 9 Oct 2013. Retrieved 27 Jan 2014.

- ^ Kluge, Alexander, ed. (1975). "Brillen". Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (21 ed.).

- ^ a b Klein, Cornelis; Hurlbut, Cornelius S., Jr. (1993). Manual of mineralogy : (after James D. Dana) (21st ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 472. ISBN047157452X.

- ^ Nesse, William D. (2000). Introduction to mineralogy. New York: Oxford Academy Printing. p. 301. ISBN9780195106916.

- ^ G. Cressey and I. F. Mercer, (1999) Crystals, London, Natural History Museum, page 58

- ^ Deer, W.A.; Howie, R.A.; Zussman, J. (2013). An introduction to the rock-forming minerals (Third ed.). London, U.k.. ISBN978-0-903-05627-iv. OCLC 858884283.

- ^ "Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 32, Beryllium and Beryllium compounds". Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ "aquamarine". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on half dozen Feb 2017. Retrieved 5 Feb 2017.

- ^ Owens, George (1957). "The Amateur Lapidary". Rocks & Minerals. 32 (9–10): 471. doi:10.1080/00357529.1957.11766963.

- ^ Grande, Lance; Augustyn, Allison (Nov xv, 2009). Gems and Gemstones: Timeless Natural Dazzler of the Mineral World. University of Chicago Press. p. 125. ISBN978-0-226-30511-0.

- ^ a b Viana, R.R.; da Costa, G.K.; de Grave, East.; Stern, W.B.; Jordt-Evangelista, H. (2002). "Characterization of beryl (aquamarine diverseness) by Mössbauer spectroscopy". Physics and Chemical science of Minerals. 29 (1): 78. Bibcode:2002PCM....29...78V. doi:10.1007/s002690100210. S2CID 96286267.

- ^ a b Blak, Ana Regina; Isotani, Sadao; Watanabe, Shigueo (1983). "Optical absorption and electron spin resonance in bluish and greenish natural beryl: A reply". Physics and Chemistry of Minerals. 9 (vi): 279. Bibcode:1983PCM.....9..279B. doi:x.1007/BF00309581. S2CID 97353580.

- ^ Andersson, Lars Olov (July 15, 2019). "Comments on Beryl Colors and on Other Observations Regarding Fe-containing Beryls". The Canadian Mineralogist. 57 (4): 551–566. doi:10.3749/canmin.1900021. S2CID 200066862.

- ^ a b c Sinkankas, John (1964). Mineralogy for amateurs. Princeton, N.J.: Van Nostrand. pp. 507–509. ISBN0442276249.

- ^ Fritsch, E.; Shigley, J.E. (1989). "Contribution to the identification of treated colored diamonds: diamonds with peculiar color-zoned pavilions". The Quarterly Journal of the Gemological Institute of America. 25 (ii): 95–101.

- ^ Kiilsgaard, T.H.; Freeman, V.Fifty.; Coffman, J.Southward. (1970). "Mineral resources of the Sawtooth Archaic Area, Idaho". U.South. Geological Survey Bulletin. 1319-D: D-108. doi:x.3133/b1319D.

- ^ Cassedanne, J.; Philippo, Simon (2015). Minerals and Gem deposits of the eastern Brazilian pegmatites. Musée national d'histoire naturelle Luxembourg. pp. 139–206. Retrieved Apr 15, 2022.

- ^ Klein & Hurlbut 1993, p. 472.

- ^ Carranza, E. J. One thousand.; Woldai, T.; Chikambwe, E. G. (March 2005). "Application of Data-Driven Evidential Belief Functions to Prospectivity Mapping for Aquamarine-Bearing Pegmatites, Lundazi District, Zambia". Natural Resources Enquiry. fourteen (ane): 47–63. doi:10.1007/s11053-005-4678-9. S2CID 129933245.

- ^ Yager, T.R. (2007). Minerals Yearbook. U.Due south. Geological Survey. pp. 22.one, 27.1, 39.three. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Color in the beryl group". Mineral Spectroscopy Server. minerals.caltech.edu. California Constitute of Technology. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved half-dozen June 2009.

- ^ Hurlbut, Cornelius Southward. Jr & Kammerling, Robert C. (1991). Gemology. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 203. ISBN978-0-471-42224-2.

- ^ "Emerald Quality Factors". GIA.edu. Gemological Institute of America. Archived from the original on Nov 2, 2016. Retrieved Nov i, 2016.

- ^ Fernie Grand.D., Due west.T. (1906). Precious Stones for Curative Wear. John Wright. & Co.

- ^ Giuliani, G.; Chaussidon, M.; Schubnel, H.J.; Piat, D.H.; Rollion-Bard, C.; France-Lanord, C.; Giard, D.; de Narvaez, D.; Rondeau, B. (2000). "Oxygen isotopes and emerald trade routes since antiquity". Science. 287 (5453): 631–633. Bibcode:2000Sci...287..631G. doi:x.1126/science.287.5453.631. PMID 10649992.

- ^ Hosaka, K. (1991). "Hydrothermal growth of gem stones and their characterization". Progress in Crystal Growth and Characterization of Materials. 21 (1–4): 71. doi:10.1016/0960-8974(91)90008-Z.

- ^ "Carroll Chatham". The Gemology Projection. Archived from the original on 10 September 2011.

- ^ Nassau, G. (1980). Gems Fabricated by Man. Gemological Institute of America. ISBN978-0-873-11016-seven.

- ^ a b c Ibragimova, Eastward.M.; Mukhamedshina, North.M.; Islamov, A.Kh. (2009). "Correlations betwixt admixtures and colour centers created upon irradiation of natural beryl crystals". Inorganic Materials. 45 (2): 162. doi:x.1134/S0020168509020101. S2CID 96344887.

- ^ Thomas, Arthur (2008). Gemstones: Properties, Identification and Apply. London: New The netherlands. pp. 77–78. ISBN978-1-845-37602-iv.

- ^ Behmenburg, Christa; Conklin, Lawrence; Giuliani, Gaston; Glas, Maximilian; Greyness, Patricia; Grayness, Michael (Jan 2002). Giuliani, Gaston; Jarnot, Miranda; Neumeier, Gunther; Ottaway, Terri; Sinkankas, John (eds.). Emeralds of the World. ExtraLapis. Vol. ii. E Hampton, CT: Lapis International. pp. 75–77. ISBN978-0-971-53711-8.

- ^ Deer, W.A.; Zussman, J.; Howie, R.A. (1997). Disilicates and Ring Silicates. Stone-forming Minerals. Vol. 1B (ii ed.). Bath: Geological Society of London. pp. 393–394. ISBN978-1-897-79989-5.

- ^ Thomas, Arthur (2007). Gemstones. New The netherlands Publishers. p. 77. ISBN978-one-845-37602-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Goshenite, the colorless variety of beryl". Amethyst Galleries. Archived from the original on 30 June 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ "Goshenite Gem". Optical Mineralogy.com. 2 March 2009. Archived from the original on ix July 2009. Retrieved half dozen June 2009.

- ^ 16 CFR 23.26

- ^ a b "Red Beryl". www.mindat.org. Archived from the original on three December 2013.

- ^ a b Ege, Carl (September 2002). "What gemstone is plant in Utah that is rarer than diamond and more valuable than aureate?". Survey Notes. Vol. 34, no. 3. Archived from the original on 8 November 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ^ "The Mineral Beryl". Minerals.net. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Ruby-red Emerald History". RedEmerald.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2007.

- ^ "Bixbite". The Gemstone Listing. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016.

- ^ "Red beryl value, price, and jewelry data". International Jewel Guild. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

Further reading [edit]

- Sinkankas, John (1994). Emerald & Other Beryls. Geoscience Press. ISBN978-0-801-97114-iii.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beryl. |

-

The dictionary definition of beryl at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of beryl at Wiktionary - . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

What Is Beryl Used For,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beryl

Posted by: lathamimption.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is Beryl Used For"

Post a Comment